Technological progress has always been designed to improve people’s lives, but rarely have these changes been painless.

The industrial revolution is usually counted from the first third of the 18th century, England is called its homeland, and the reason is technical inventions that ensured the transition from manual labor to machine labor.

There are many views on this process. The term itself appeared only in the 19th century. There are authors who believe that the industrial revolution began in the 13th century with the spread of mills. Already at the end of the 15th century, the first blast furnace, printing press and mine water pump started operating in England. In 1482, the English Parliament established that hats made by “human effort” were superior to those made by felting machines. Apparently, there were already enough cars to create competition for manual labor and the conflict was large-scale, since it came to parliament.

The plagues of the fatherland and the singing weavers

To better understand the nature of the industrial revolution and the contradictions inherent in it, one must agree that it is not a matter of simple mechanization of labor. Mechanical innovations have been known since antiquity. Until the 18th century, the Netherlands, Germany and Italy experienced economic ups and downs – many of the British achievements were the result of industrial espionage. Spain had no fewer colonies than England. The Industrial Revolution is more than that; she was both cause and effect and part of social change.

In England, the end of the 15th century was the period of the end of the feudal wars and the beginning of economic growth. The “merchant king” Edward IV became the first monarch in 200 years who did not leave behind debts. In England, there were “new nobles”, gentry, who did not just receive rent, but were active in economic activity. They relied on sheep breeding and cloth making, expelling thousands of peasants from their land.

Mass vagrancy aroused the indignation of the authorities. “Due to the conversion of land to pasture, which was usually under arable land … in some villages, where previously two hundred people found employment, now two or three shepherds are employed, while others fall into idleness,” the parliamentary bill of 1489 announced angrily. Wool manufacturing spread to the countryside, leading to the decline of craft centers in the cities.

In the 16th century, the process gained momentum. The crowds of the poor have become a real scourge. “What else is left for them but not to steal and end up on the gallows, or to wander and beggarly?” – Thomas More, author of “Utopia” laments, criticizing the aristocratic sheep-breeders. The impoverished peasants often had no choice but to hire them for factories or mines. Poverty turned out to be, one might say, the original sin of industrialization. She fought poverty and gave birth to it.

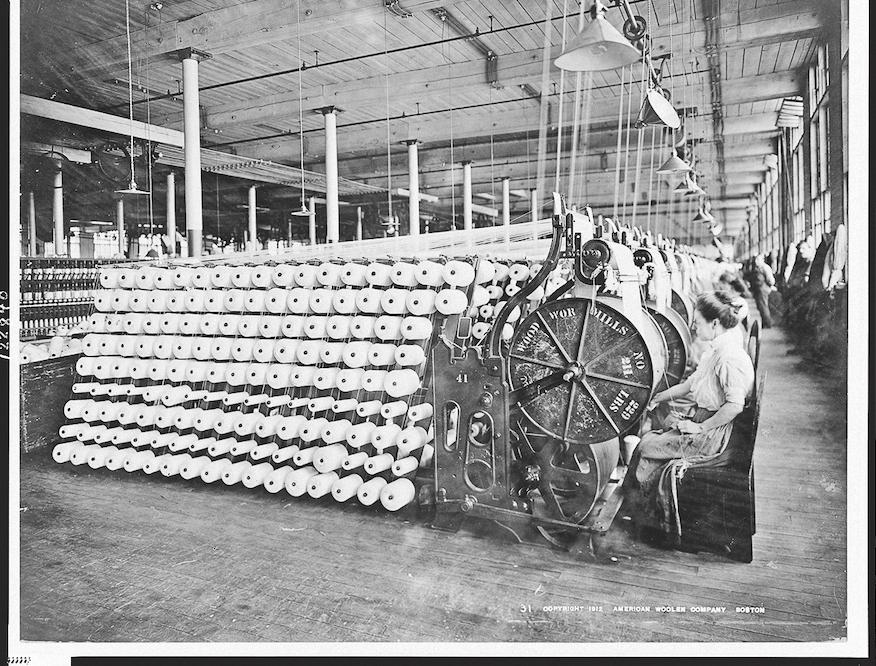

However, someone perceived what was happening positively. The writer Thomas Delaunay (1543-1600), in his novel Jack of Newbury, describes a large manufactory: “In a large and wide workshop there were two hundred machines, and two hundred people worked at these machines. A pretty boy sat next to each of these workers and cheerfully drove the canoes. In another hall, two hundred merry gossips with all their strength combed wool and, while working, sang all the time. ” In the next hall “two hundred young girls in red skirts with white headscarves” work – they spin all day, “never interrupting their work,” and they also constantly sing “with gentle voices like nightingales.” Next come the children of the poor, sorting wool, – they receive a penny a day, “not counting the fact that they were fed throughout the day, and this was a huge help for them.”

The dyers, the felts, the ironers are all well-built and constantly singing. The idyll looks implausible given what we know about working conditions at that time, the modern reader will pay attention to both child labor and the continuous work of spinners, but the author himself was a weaver and knows what he is writing about. Apparently, the situation in a large enterprise delights him in comparison with what was happening in small workshops.

Remelting consciousness

The revolution needs preparation; for a century and a half, Europe, and England in particular, broke with feudalism. The old aristocracy was leaving – the number of serfs was no longer an indicator of prestige, money became the measure of success. Ordinary people lost their roots with the land. The peasant, the head of a large family, would hardly want to change his occupation, but people deprived of everything became inclined to risk, receptive to new things and more tolerant.

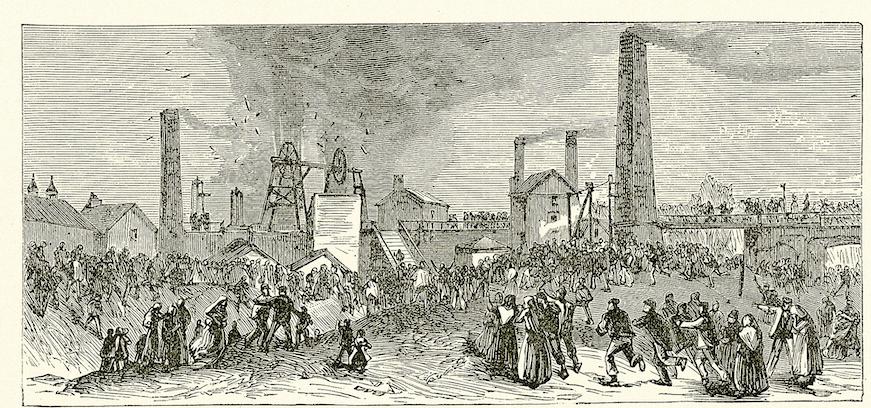

Under the pressure of the new rural industry, the old guild organization was breaking down, although the guilds remained for a long time a stronghold of reaction. Thus, the ribbon loom was invented in Danzig in 1579, but the inventor, according to legend, was drowned; this machine was re-invented a quarter of a century later in Holland. A century and a half later, John Kay, who invented the “flying shuttle” for the loom – one of the symbols of the industrial revolution – was forced to flee to France from the wrath of his fellow weavers. There are many such examples.

The new industrialists ignored guild rules, such as the apprenticeship of future masters. City artisans protected, as they would say now, the rights of small and medium-sized businesses. And they were crushed by the paradoxical, forced alliance of the nascent oligarchy and the proletariat.

Reforging the consciousness of the medieval inhabitant was in full swing – the Church Reformation, the Renaissance, the development of the New World. Their common denominator was the liberation of the mentality of the people. A person learned, in principle, to quickly and willingly adapt to everything new, including food, change living conditions, be mobile, exchange information.

The symbolic peak was the English Revolution, when Charles I was executed in 1649 – for the first time the people took the life of their monarch, and this example is important to see to what extent the readiness of the English has reached the willingness to renounce traditions. Scientists argue about why the industrial revolution took place on the island – it is possible that it was political innovations that became the “philosopher’s stone”.

In China, for example, absolutism, with its craving for stability, has deprived society of the dynamics of progress. In the Islamic world, the achievements of the “infidels” were totally intolerable. “Because in Europe, technical change was driven by private actors in a decentralized, politically competitive environment, it could take place over time, make big leaps and never lose momentum,” says historian Joel Mokier.

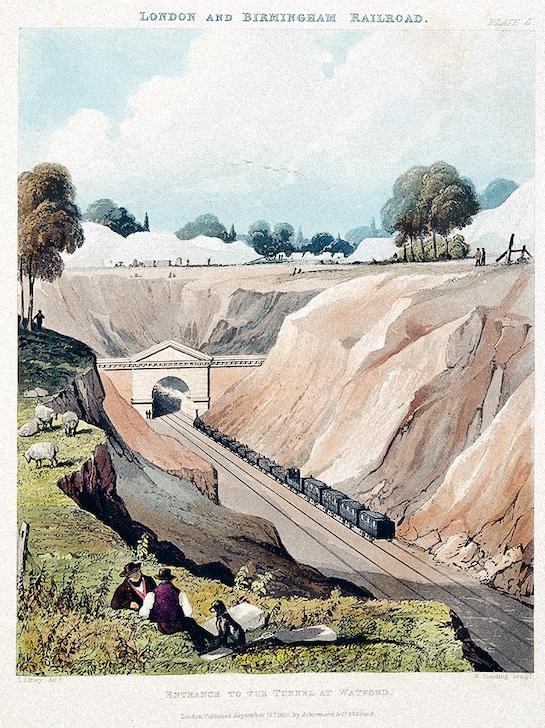

Europe adopted inventions from the East – but not vice versa, and in a broad sense, the industrial revolution also ensured the Eurocentricity of the world. Cynicism turned out to be the reverse side of the craving for personal freedom – the slave trade actively expanded. Empires began a dispute over the colonies, trade grew rapidly, which means that shipbuilding and insurance developed; canals and toll roads were built. The beginning of the 19th century is the start of the railway era, and England is again becoming a pioneer.

Big leaps

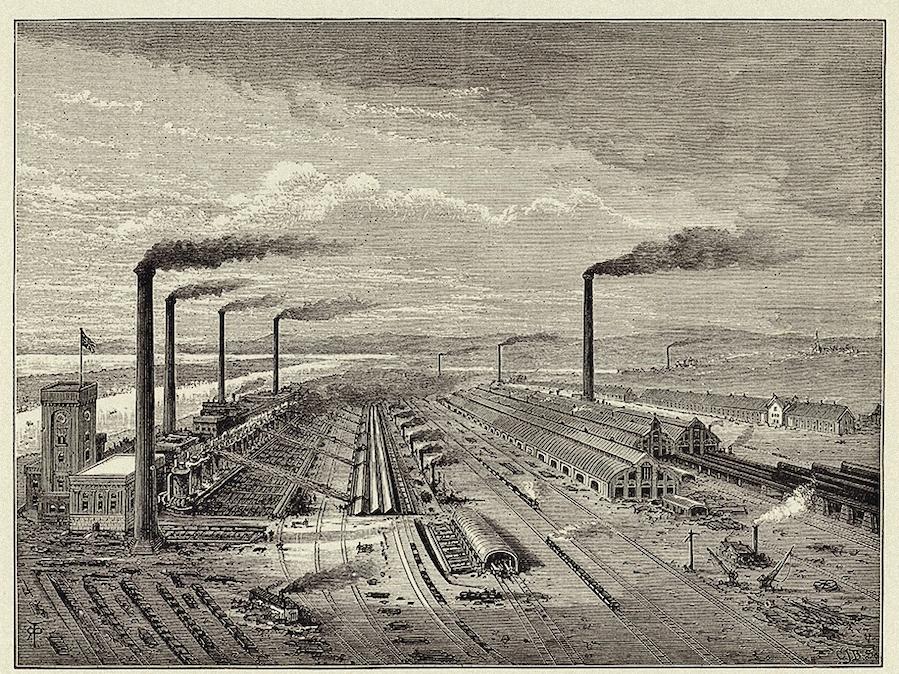

The population in Britain has grown steadily since the 16th century, increasing unemployment and poverty on the one hand, but consumption on the other. Agriculture had to make a big leap forward; small owners balanced themselves, becoming either large farmers or wage laborers. The authorities issued law after law obliging the able-bodied poor to work. The coal mining industry is rapidly emerging – miners, mostly landless peasants-settlers, were at the very bottom of the social ladder.

The development of trade led to the growth of cities, which became an avalanche. The poor concentrated in the workhouses, forming what Karl Marx would call the “industrial reserve army.” Soon it will rush to factories.

Alexis de Tocqueville in 1835 describes, for example, Manchester as a real hell: the city’s population increased tenfold from 1760 to 1830, reaching 180 thousand people. For the most part, they were all the working proletariat, immigrants who lived crowded and meagerly. They, like women and children, could hardly be paid.

It was already impossible to stop. New challenges were popping up; Thus, the colonization of India provoked a flow of cheap fabrics, the local industry had to respond with its own cost reduction, achieved through technical innovations. Invention plus the development of ideas of property gives rise to the development of the patent system (it dates back to the 15th century in Venice) – innovators could already make money.

Early marriage became the norm, prompting a new surge in demographics. People demanded welfare, new goods – industry could make them cheap only by saving on labor.

By the period that is conventionally called the “second industrial revolution” (the second half of the 19th – early 20th centuries), both innovative and social trends deepened. The Suez Canal was dug, a telegraph cable lay along the bottom of the Atlantic – but the negative also accumulated. The power loom has become a “real social disaster,” as the historian Fernand Braudel puts it: “Thousands of unemployed were thrown into the street, wages dropped so much that the now negligible cost of labor extended manual labor beyond reasonable limits. labor of unfortunate artisans ”.

Unsurprisingly, there has been an upsurge in the Luddite movement trying to destroy cars. However, progress did its job: workers’ wages were still growing steadily, blue-collar factions, part of the “middle class” that benefited from industrialization, stood out from the masses of the disadvantaged. The second stage of the industrial revolution highlights not only the invention of electricity and gasoline, but also the fact that population, prices, GNP and wages begin to grow in industrial countries at about the same rate.

The position of European workers improved, among other things, due to the emergence of new centers of cheap labor in Asia. And nevertheless, if inequality between societies grew, then within society it was smoothed out. However, too slowly, and in the middle of the 19th century, trade unions appeared and soon – Labor and Social Democratic parties. The second important movement is that the desire of states to keep up with their neighbors in development takes on the character of competition and leads to the development of nationalism. Both of these processes will eventually converge at the point of the First World War and revolutions.

Revolution and globalization

Globalization was what ensured rapid development at this time. In the first half of the 20th century, the era of wars, isolation and decolonization, the trend was undermined. The pause was probably necessary to even out the effects of social crises – but at the same time it highlighted the chasm between countries. For the most part, the former colonies have not been able to bridge the technological gap.

Only in the 1980s, with the fall or transformation of communist regimes, globalization resumed. The countries of Asia, having agreed to join the channel of the West, received economic growth. Computers and mobile phones would surely have been invented anyway, but without globalization, this would not have acquired the character of a revolution. Again, we see the same reasons and the same consequences: freedom as a driving force of development, global stratification, the growth of cities with armies of ancillary workers providing best practices (like couriers to online commerce), the dissolution of small entrepreneurs, undermining labor relations, and so on. Progress raises the quality of life for everyone, but thereby also raises the bar of demands – grassroots social movements are again becoming relevant.

If we consider Industry 4.0 as a logical continuation of the process, then the fears remain the same: after all, robots can turn out to be the same social disaster as the power loom used to be. And only a few workers in the advanced sectors of the economy will benefit.

The gains of the winners must this time be significantly higher than the losses of the losers in order to be enough to compensate. Otherwise, humanity runs the risk of breaking the brake again, as at the beginning of the 20th century. However, this will most likely be just another suspension, but not the end of progress.